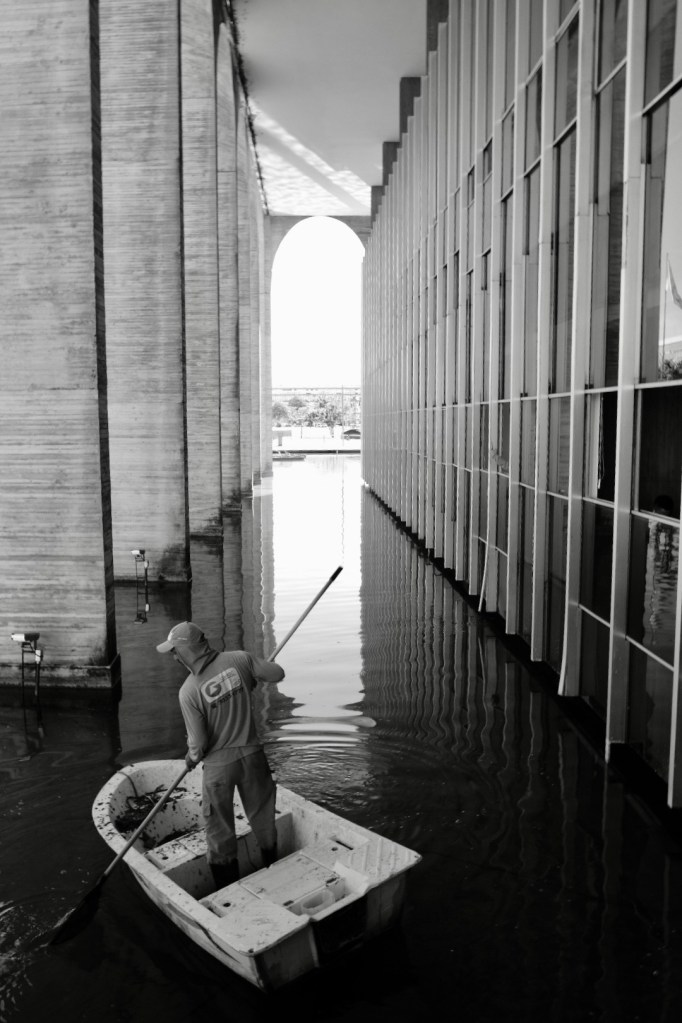

This was my first visit to Brazil and the first thing I did was visit the Brazilian Parliament. Starting from the Southern Hotel Zone where I was staying, my walk took me past the new national library, a museum that looks like a moon base, the municipal cathedral that looks like a cake, and a series of stacked rows of buildings holding government ministries – from defence and the interior, culminating in the Oscar Niemeyer designed Palace of Justice and Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Brazilian is a planned city designed in the shape of an aeroplane. The north and south wings of the plane contain residential blocks, the east west axis is a grassy esplanade. The plane isn’t visible from ground level, but from maps I knew my route was taking me down the fuselage towards the National Congress building which sits in the cockpit. It’s a city made for cars – like airplanes they fit in the modernist imagination as the transport of the future – but walking was easy enough along a broad avenue of shady trees, cycle paths, brown grass, ponds and fountains.

The National Congress Palace – the home of Legislative Power in Brazil – reveals itself suddenly because it sits in a little dip. The flat roof is level with the land around, cars and busses wiz past on the highway. The right side of the National Congress building’s roof is covered by a bowl and the left a dome. The dome sits over the Senado Federal (senate) and the bowl covered the Camara dos Deputados (the chamber of deputies). It’s not immediately obvious how you enter – there’s a gleaming white ramp up the centre and on both sides are roads down. There aren’t many people around so I’m not able to follow anyone. I take one of the roads down. It turns into a drop off area in front of the glass entrance to the building. Getting in is straightforward and the staff are friendly – after a security scan I’m given a lanyard and asked to sit on one of the low slung deep leather sofas (the public furniture was designed by Le Corbusier and Mies Van Der Rohe). The public tour will start in ten minutes.

Tours of the National Congress Palace are conducted in Portuguese which I don’t speak. The thoughtful staff provided me with a six page printed text in English which I read as I waited for the tour to start. From it I learned that I was sitting in the Noble Hall of the Chamber of Deputies and that the artwork in front of me was by the Franco-Brazilian plastic artist Marianne Peretti. The text went on to list the coloured halls (Black, Green and Blue) on two levels that sit outside the two chambers and the artworks displayed in them – oil paintings, works in stained glass and bronze statues. The final part of the text explains the composition of the National Congresso. DESIGNED BY Oscar Neimayer

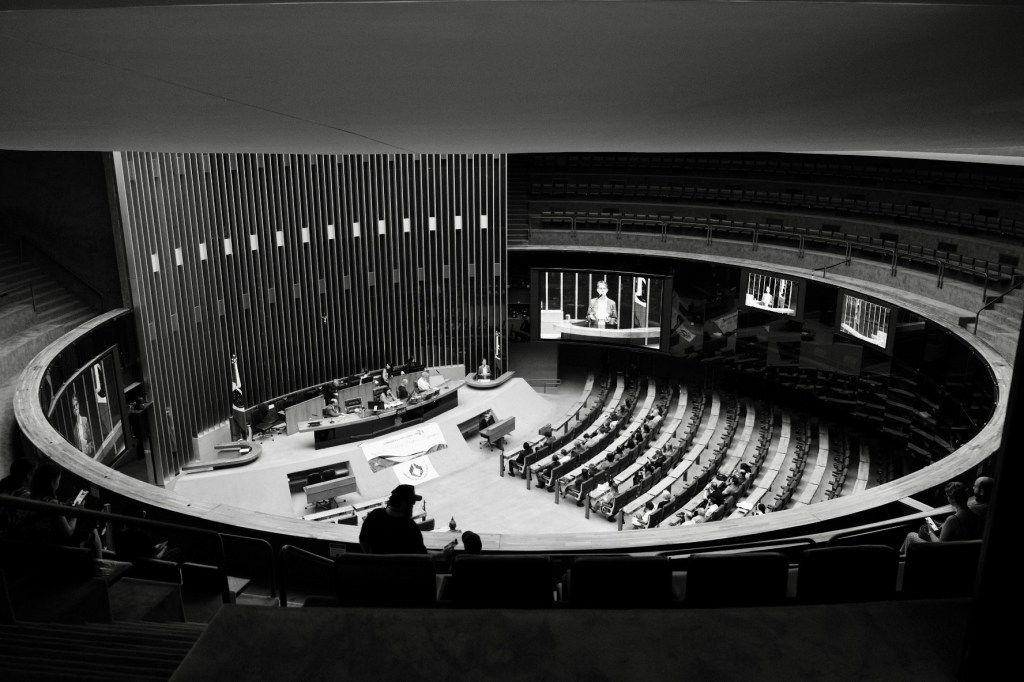

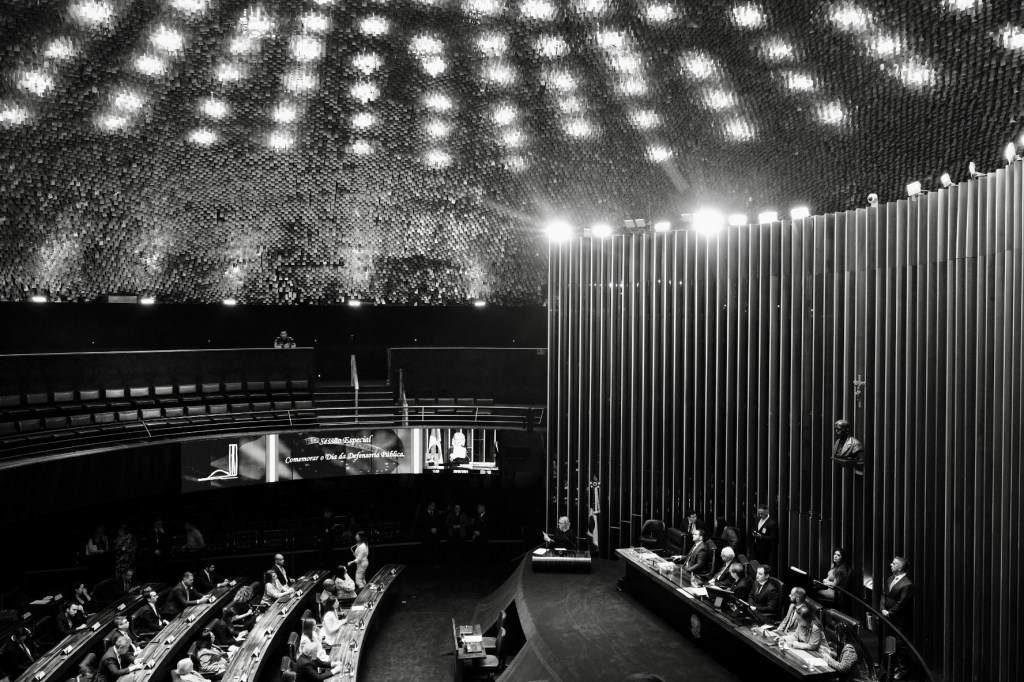

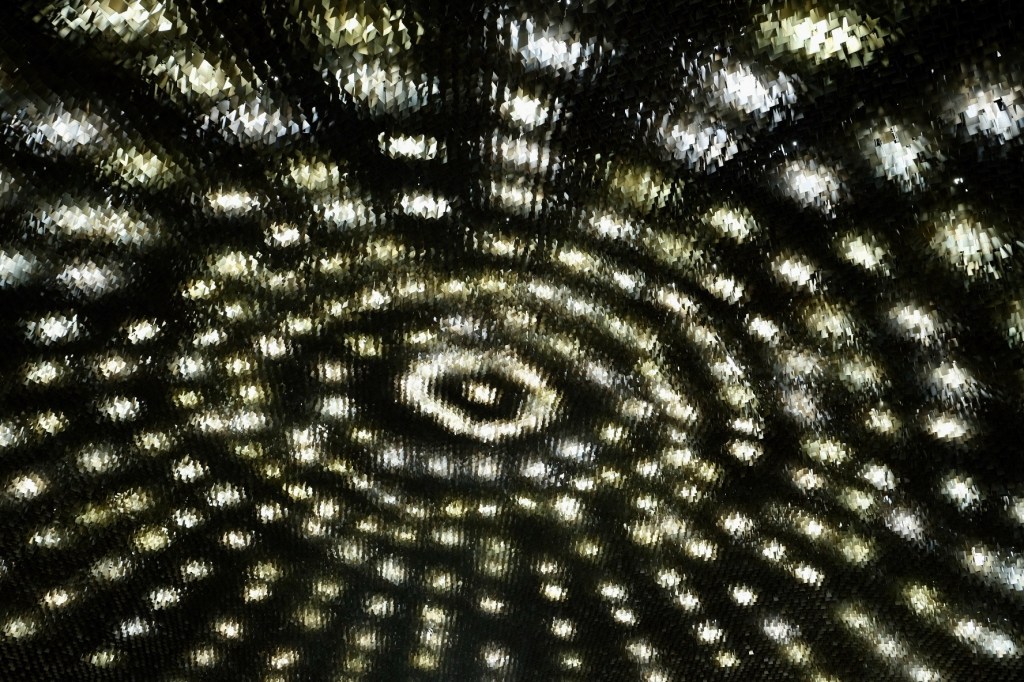

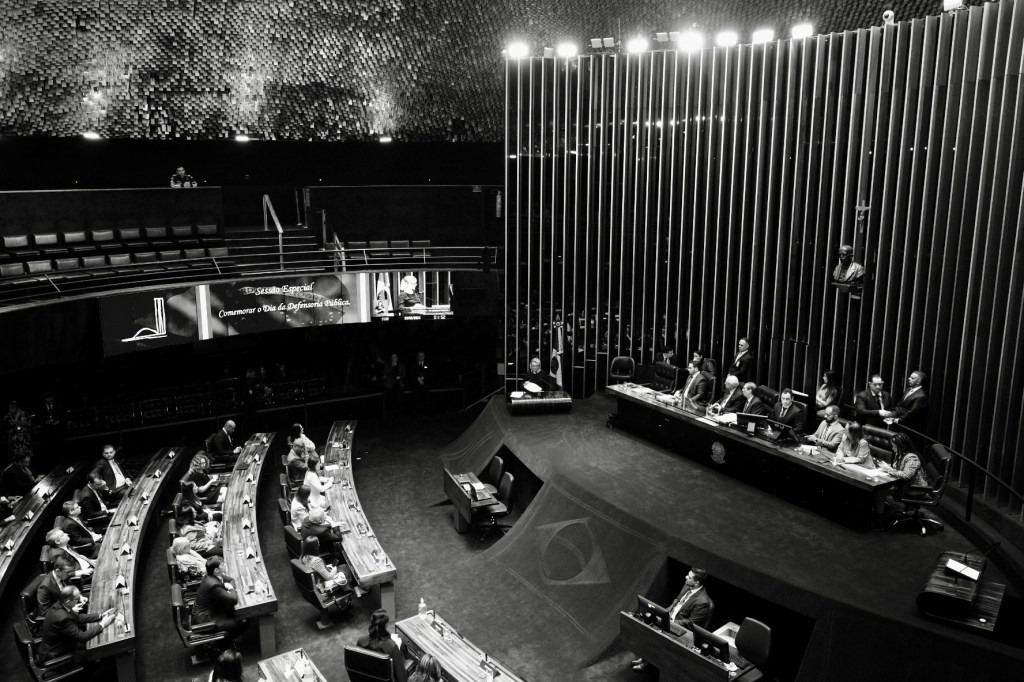

Not speaking Portuguese meant I couldn’t participate fully in the tour process but this provided me the opportunity to observe the others who did. Our group of twenty were mixed in age – from school age to retirement age. They looked wealthy and mainly were dressed in casual clothes – shorts and strappy tops – though one young man wore a snappy black suit and white shirt. Our guide was in her twenties – well-dressed but not formally dressed, she spoke clearly and confidently, and the group listened respectfully and asked questions. We moved from one set-piece to another – the area outside the chamber where TV crews line up to interview deputires as they enter and leave the Plenary, the time tunnel which tells the history of Brazil’s parliament, a scale model of Brasilia’s cockpit. There were lots of selfies taken – next to statues, in front of paintings, and, particularly popular, beside the long window where the 27 flags of each federal state are displayed (holding whichever of the line of flags represented the state they had come from). We were marshalled physically but also underlying tone of tour was of confirming the relationship between the nation and it’s citizens as articulated historically, constitutionally, through regional identity, people and regions coming together in difference. Around us the National Congresso went about its daily business – men in suit talked and walked, TV camera men waited with their equipment for the next deputy to interview, groups of schoolchildren were ferried round on their own tour. The climax of the tour came at the end: we were invited to view first the chamber of deputies and then the senate from the public gallery. The first has an inverted roof which sags down – the bowl sitting atop the building; the second had a beautiful dome dotted with lights that shine like starts in a night sky. The tour completed I wondered where were the people – Brasilia as a city and the National Congress as a parliament felt strangely empty. I was told that Mondays are a slow day in the Congress; deputies are returning to the capital after spending the weekends at home.

It turned out that the people appear on the Tuesday. My second full day in Brazil starts with a protest march – at 8am three lanes of the six-lane fuselage highway are occupied by farmers and agricultural works campaigning for land reform. The march is colourful and loud and takes nearly an hour to pass. They are heading in the direction of the National Congress. Cars and buses are backed up in a lengthy que behind the march.

My plan for the day is to return to the National Congress. Today though I won’t go alone for I’m accompanying my friend Tiago – a filmmaker. Tiago wants to lobby deputies to support a bill imposing a tax on screening giants like Netflix. The idea is that any money generated can be used to support budding Brazilian directors, writers, and producers. But first we have to buy ourselves ties – to be worn with jackets when passing outside the chambers. Shopping completed we enter the Parliament via Anex 2 – a low and fairly non-descript building sited next to the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate. Anex 2 contains committee rooms, lecture theatres, plenaries (behind it are the two towers of Anex 2; Annexes 3 and 4 house the personal offices of the deputies, restaurants, a travel agency and post office) Tiago is well used to visiting the Congress – he spent six weeks here making the documentary film A Camara. Yesterday the parliament felt empty and our movement of our tour group was carefully planned. Today the overwhelming feeling is of chaos The corridors, plenaries and committee meeting rooms team with people – from the march for land reform, Mayors from Brazil’s cities begging funds for their municipalities, a group of Israelis handing their flag to a group of right-wing deputies. The impression I get is of a busy marketplace on the day when everyone comes to town. I follow Tiago as he bounce between deputies’ offices explaining why they should support the bill . taxing the streaming giants. They listen and also update him on how those opposed to the proposal are spinning the measure as an additional imposition that will increase the cost of subscriptions for ordinary Brazilians. Though we pass by the Chambers of the sentate and the Deputies several times we spend most of the day in annexes where most of the everyday work of the National Congress go on. These are closed and self-contained spaces in which windows are few and far between. Opportunities exist to grab a glass of water or a cup of coffee.

Brasilia is a city based on an idea of linear progress – but cars and aeroplanes represent a dream of a future that once was. The National Congress, teaming with the hope and ambitions of millions, strives to maintain the possibilities of democracy.