The Hindi word ‘ghumantu’ – roving, mobile, wandering – also translates into English as ‘itinerant’ – a word with considerable negative connotations. The stereotypes that attach themselves to the term, however, have not stopped both Gaddis and Gujjars in Chamba District from laying claim to it. My friend and research assistant Uttam said ghumantu refers to ‘people who travel’ and this can either mean families who move from a summer to a winter home each year and also refers to groups of men, such as Gaddi shepherds or labourers, who go away to work. Gulzar – a Gujjar who I spent some time living with – disagreed; according to him only his people are ghumantu as they, unlike the Gaddis, travel as family groups taking their homes and animals with them. He said the difference was that while Gaddis ‘look to their land first, we Gujjars look to our buffalo’. Gulzar makes a good point: over the last twenty or thirty years most Gaddis have given up their traditional shepherding. For many Gujjar families, on the other hand, the rearing of buffalo and the selling of milk remains a key component of household incomes. Furthermore, as I went about gathering genealogies during the early stages of my research in the upper part of the Saal valley, I discovered that almost every Gujjar family had a brother, sister, son or daughter who had left to live permanently in Punjab. If I was to understand the lives and life chances of the Gujjars of the Saal valley it was clear I needed to understand the reasons these people were leaving, where they were going and what they were doing when they got there.

Gujjars in Chamba District

Migratory Gujjar buffalo herders are found across the western Himalayas from Jammu and Kashmir, through Himachal Pradesh and on to Uttarakhand. For centuries these herders have exploited an ecological niche that exists where the plains of Punjab and Uttar Pradesh bump into the foothills of the Himalayas. Across this zone Gujjar families spend the winter in low lying areas before moving with their buffalo up to alpine pastures during the hot summer months. They stay at these summer dhars until autumn when, as temperatures drop and snow begins to fall, they retreat back through the Siwalik hills to their winter homes. This traditional system of tranhumance nomadism permits the Gujjars to access greater amounts of fodder then if they stayed in one place year round. The literature describing this form of migratory pastoralism usually presents it as being in decline – the expansion of agriculture, urbanisation and state pressure to settle have forced many Gujjar families to sedentarize.

Gujjars first brought their buffalo to the Princely State of Chamba towards the end of the 19th century. The families of the Saal valley generally agree that their origins are in J&K and that they came to Chamba at the invitation of the then Raja. At that time hereditary ‘traditional rights’ to reside at, and obtain fodder from, certain alpine grazing ‘dhars’ was granted by the Chamba State. Administered by the Forest Department of Himachal Pradesh these rights – asserted in named individuals – are retained today. Those Gujjars whose grazing dhars are in the upper parts of the Chamba valley typically spend the winter months in the northern districts of Punjab. They sell milk in villages and towns around their winter residence and then, at the start of the hot season, walk for up to 20 or 30 days to reach their permit pastures in Chamba District. There are however variations within the usual pattern of Gujjar transhumance nomadism. Other Gujjar families have opted to live year-round in Chamba District – usually those that have land in the low lying regions close to the district capital Chamba town including in the area around the river Saal where I do my research. Having taken up farming many of these families choose not to migrate though, even when sedentary, they continue to combine buffalo rearing with agriculture. Typically these Saal valley families feed their buffalo with grass cut from local hillsides in autumn and stored to last through the winter. In the summer months, those that choose to, take their animals from their homes close to the Saal river up to alpine grazing pastures that overlook the valley. This journey takes only one or two days and there is much back and forth between the pastures, home villages and Chamba town where milk is taken daily to be sold. Though a significant minority still migrate each year with their animals, most of the Gujjars in the Saal valley grow wheat and maize at their village homes and supplement this with employment as mazdoors either around Chamba town or further afield doing ‘project work’. Others have benefitted from ST status to become educated and secure good jobs in the government, the private sector or in business. While this would seem to confirm the usual picture of nomadic decline, it became apparent that there is a counter narrative to the story of sedentarization. Upon commencing research in the Saal valley it soon became clear that a significant number of families had sold their land in Chamba, given up their traditional Alpine grazing dhars, and taken their buffalo to Punjab year round.

Between December 2014 and July 2015 I travelled three times to Punjab to meet these ghumantu families.

- In December 2014 a preliminary visit with my friend Tittu Hussain Lodhi was my introduction to Gujjar buffalo herding in Gurdaspur and Hoshiarpur Districts of northern Punjab. Talking to farmers and town people I was able to get an impression of the sorts of agricultural changes that the area was undergoing and gain an appreciation of the value placed on the desi buffalo milk that the Gujjars sold to them.

- Tittu has relatives who now live in Malerkotla – a tehsil of Sangrur District in Southern Punjab. For three roasting hot days in April we visited them and went on to interview families living in four nearby Gujjar settlements before returning to Chamba via Phagwara and Tanda where other Chamba Gujjars are now living. It was during this time that I met Jan Mohammed, Master Hanif, Noor Hassan and Shaif Mohammed for the first time.

- Tittu was not available in July so for my final visit to Malerkotla I was accompanied by my friend Sunil Kumar. We stayed with Tittu’s sister and her husband Jan Mohammed in the by now very muddy Gujjar colony at Naudharani. For two full days we accompanied Jan Mohammed with his buffalos through heavy monsoon rains as they went out on their daily search for grazing. On our last morning in the Gujjar colony we visited a madrassa that has been established with money donated by the community. Back in Malerkotla city we also enjoyed an audience with the former Begum of Malerkotla (now aged 101). We spent a further three days in the company of Shreya Sinha finding out about wider processes of agricultural change in Sangrur District, industrial expansion around Malerkotla and the impacts of these processes on land prices and uses. With Shreya we visited a Super Dairy and a rice mill, met a Chicken King and a Muskmelon-King, interviewed a commission agent in Malerkotla’s main agricultural market and spoke with several dhodis and Jat farmers.

This paper will consider the forces that drove Gujjar families to leave Chamba and the process of migration as it has evolved over the last three decades. Many of the families that left the Saal valley have relocated to Sangrur District of Southern Punjab and, in particular, an area to the south of Malerkotla city. The second part of this paper will take us to Malerkotla to outline agricultural and industrial development in the area and the establishment of a niche for Gujjar buffalo herders dependant on new sources of fodder. This extends to consider the conditions of Himachali Gujjars after the shift to Punjab and how their position compares to that of those remain in Chamba District.

Leaving Chamba: Relocating in Punjab

The first family to leave from the Saal valley was that of Shaif Mohammed. That was in 1980 and they relocated in Thana village just off NH1 to the north of Jalandhar. A few years later the brothers Fateh Mohammed, Noor Hassan, Saukhat Ali and Ismael decided to leave Saho and, by 1995, had settled in Malerkotla. Others followed. The initial trickle of migration grew into a large wave in the mid-1990s. One informant told me that ‘in the four panchayats here [in the Upper part of the Saal valley], if there are four brothers in a family then two will go to Malerkotla and two will stay’. This, I think, is an exaggeration. Another estimate – that approaching 500 families from Chamba District are now living in Punjab – seems closer to the truth. It is difficult to identify any common socio-economic background of those Gujjars that left for Punjab: there is no sense that those that left were any more deprived that those that stayed; most (but not all) owned land in Chamba and family members who stayed behind span the spectrum from the poorest to the relatively well-off. What does unite the Chamba Gujjars that left for Punjab (and is echoed by those that remain) is in their explanation for why they left. Though some cited additional factors (family disputes, being unable to find work in Chamba, low pay) the overwhelming reason that people gave for leaving Chamba was a lack of adequate grazing land and the high cost of fodder. That fodder supplies do not meet needs can, in part, be attributed to the administration of grazing permits issued by the Forest Department. These provide a named individuals with a hereditary right to graze at a particular place a fixed number of animals (deemed to be the carrying capacity of the pasture). But, being passed down from father to son(s), it follows permits have been split and split again over the generations. As the number of Gujjar households has increased so individual families are ‘permitted’ to take fewer and fewer animals up to their dhar. However, the immediate trigger that persuaded so many Gujjars to leave Chamba was not the condition of their summer grazing. Instead in late 1996 it appears that it was an acute shortage of the winter feed gathered from village grass reserves that forced buffalo owning families to look elsewhere.

Shaif Mohammed is a big man in every respect. Now firmly established in Punjab he lives in a large two-story kote. Seated on comfy chairs in Shaif’s large reception room where we offered tea and lassi. Chain-smoking unfiltered cigarettes Shaif told me how in his childhood he’d travelled to Punjab with his family’s buffalo in the winter months: ‘I’d seen there that there was so much greenery and good crops and plenty of fodder so I though why not come here?’ But migration out of Chamba was not a simple or singular process. Shaif Mohammed spent fifteen years shifting from place to place: ‘in the first seven years I moved residence seven times’. This is echoed in the accounts I gathered from other families who recalled spending months or years at a time living on plots rented from farmers or on land belonging to the Forest Department. Over time it is possible to trace how these families gradually shifted south following the route of NH-1A and NH-1 from Pathankot to Jalandhar, Phagwara and Ludhiana. As they moved they found work along the way – caring for the buffalo of Jat farmers or helping with harvesting in return for cash or fodder. Most families left Chamba with only a few buffalo but, over time, they devoted their efforts to adding to the size of their herds. A female buffalo might cost upwards of 30,000rs (the best milkers can go for 60,000) but sellers might accept an initial down payment with the balance paid in instalments. These were not easy times: I was told that landlords might unexpected hike up rents, the Forest Department didn’t look kindly on encroachment and if repayments couldn’t be met then lenders could seize their buffalo. But milk prices are comparatively high in Punjab and many families were able to increase the number of buffalo they kept. With enough buffalo they no longer needed to do kheti-ka-kam and could instead devote themselves to their animals. Says Shaif Mohammed: ‘everything here is brought and sold’; he and the others that followed him went from ‘producing the milk, to selling the milk, then using the money to buy more buffalo’. For most the next step was to buy land – just enough to construct a house, stall your animals and store grass – but a foothold nonetheless. Shaif Mohammed settled close to Urmar Tanda in Hoshiarpur District; others continued further South until they reached Phagwara and Malerkotla

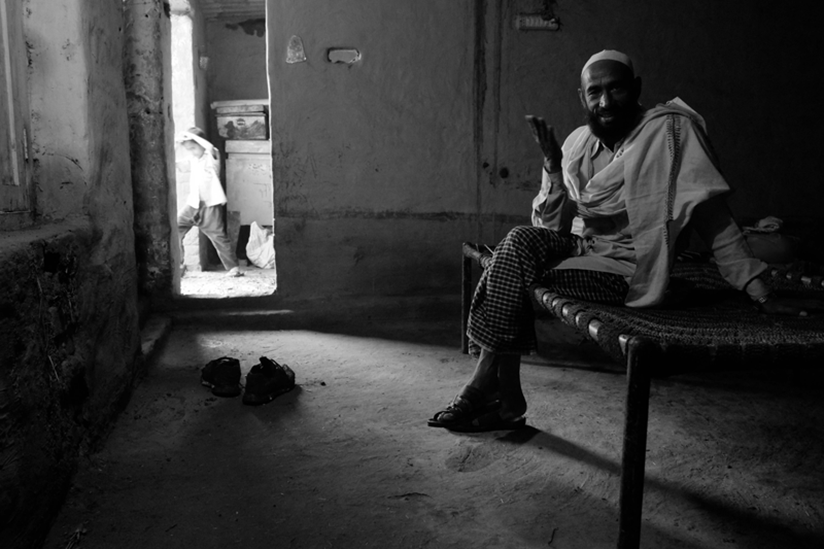

Figure 1: Noor Hassan Lodhi

A large brick-walled courtyard surrounds the house of Noor Hassan Lodhi. The one-storey building has only two rooms but they are large and the walls have been plastered and whitewashed. A pile of cut paddy straw towers over the house. From Noor Hassan I learned that his brother Fateh Mohammed was the first of the Chamba Gujjars to arrive in Malerkotla. Other Gujjars followed Fateh Mohammed to the Malerkotla area including Noor Hassan. After several years renting land from farmers, in 1998 the brothers were is a position to club together to purchase 6 bighas (1.5 acres) of unirrigated land about 5km south of the town. The cost of the land was 185,000rs per bigha which they were able to meet by selling some of their buffalo.

Set back from the main road, the Gujjar colony at Naudharani has a rice-mill to its rear and a magnificent ranch-style house to the other side. Behind this mansion and in clear sight (and smell) of the Gujjar colony is a poultry farm – huge multi-storey sheds that are home to many thousands of chickens. Pind Naudharani – a large and prosperous village – lies across fields some way to the south. Since the founding of the Gujjar colony other families have come to live here. Adjoining land was added to the original 6 bighas – the cost being funded through the sale of buffalo and loans provided by relatives. Now 14 households are contained with this space – all originally from the upper part of the Saal valley or adjoining Silagarat. Electricity was soon provided to the site but the families had to club together to finance the construction of a tube well. At the entrance of the colony is a new concrete mosque with a block for washing that was built by the whole community with the help of two lakh rupees gifted by the local MLA. In the words of retired school-teacher Master Hanif, Naudharani is a place where ‘everyone shares in happiness and sorrow’.

Agricultural and Industrial Development around Malerkotla

To a newcomer from the hills the flat landscape of southern Punjab appears wholly alien. The countryside here is regulated into a seemingly endless expanse of rectangular fields of verdant well-watered paddy and abundant vegetables crops. The fields are occasionally broken by four-square concrete houses hidden behind high walls. Overloaded tempos putter down long straight roads lanes followed by expensive tractors and pick-ups weighed down with sacks of produce. Malerkotla, like Chamba, was a princely state. Unlike Chamba it has a majority Muslim population and a major hub of vegetable production in India.

Noor Hassan explained to us the sociology of the Malerkotla area:

‘First there are the Muslim business-men and shop-keepers who live in the city. Then there are the Jats – Hindus and Sikhs that own most of the land in the countryside around the city. The third group are Scheduled Castes. The fourth group are called Kumaon [spelling?] – these are Muslims who have to work for others as agricultural labour but also have a little land of their own’.

What is unique about Malerkotla town is that it is the only place in the Indian Punjab that has a majority Muslim population. In Punjab as a whole the 2011 census records 57.6% of the population as following Sikhism, 38.5% as being Hindu and 1.93% as being Muslim. These figures are reversed in Malerkotla where 68.5% of the city population follows Islam, 20.7% identify themselves as Hindu, and Sikhs make up 9.5% of the population. Famously Malerkotla was the only area of Punjab spared the violence of partition. Since 1962 the constituency has sent an unbroken line of Muslim MLAs to the Punjab Assembly. Noor Hassan said he feels comfortable in the presences of so many co-religionists: ‘there are many mosques, the place is very religious’.

Though Noor Hassan didn’t mention it there is also a large amount of migrant labour at work in Punjab. Planting, weeding, transplanting and picking would, in the past, have been done by landless Punjabi Dalits; now this work is done by workers recruited from Bihar and Jharkhand.

Shreya provided an overview of agricultural development in southern Punjab:

- Pre 1947 all landowners in Punjab were Jats who let the land out for sharecropping by tenant farmers.

- In the decades after Independent the Jat landowners sought to bring their land back under direct control. Sharecroppers were evicted and replaced by attached labour (naukar/sanji) and / or wage labour.

- Through the 1960s and ‘70s landholdings were consolidated and farm sizes increased. Small farmers sold out to big farmers. Farming became more capital intensive.

- While earlier the main crops were course cereals (inc millet), cotton and groundnut, with the green revolution came new varieties of wheat.

- Paddy cultivation began in the late 1970s and expanded through the 1980s. The labour needed to plant, transplant and cut the paddy is recruited from Bihar, UP and Bengal where they are experienced in the cultivation of rice. The rice growing season is May to October (Kharif). Rice is milled in October; after harvest prali is burned in order to clear the field for the next crop.

- Over time the cost of land has gone up but this is especially true since 2005. Around Khanna (where Shreya is based) a year’s lease on good agricultural costs up to 50,000rs for a year’s lease. According to Shreya in that area the Mahajans complains that now even they can’t afford to buy.

Two other factors specific to the Malerkotla area were uncovered during our time there:

- The Malerkotla area is famed for its vegetable production. In the past famers in Malerkotla had grown onion, garlic and cereals but had now shifted to okra, cauliflower and cucumber.

- The area to the south of Malerkotla is a declared industrial zone. In 1981 the Vardhman Group established a Spinning Mill employing 1800 people on a 62 acre site. Since the late 1990s speculation on agricultural land near the Naudharani Road accelerated as this industrial area expanded.

As we shall see, these factors combined to influence the migration of Gujjar buffalo herders to the area.

Figure 2: The Gujjar Colony at Naudharani (red marker); Outskirts of Malerkotla at top

The Economics of Buffalo Herding in Punjab

Those Gujjars who keep buffalo in Chamba District combine their pastoralism with agriculture and other income earning activities (typically labouring). My survey of 48 Gujjar household in the Saal valley recorded 34 families as owning buffalo of which only 14 sold milk commercially (29% total). In contrast those who leave for Punjab devote themselves almost fully to their animals and are dependent on the sale of milk for their livelihood. Though some of the younger men at Naudharani have found employment (three irregularly as drivers, one working part-time in a shop for 5000rs per month), out of the 14 families living in the colony all bar one own between 10 and 30 buffalo. This pattern was repeated across all of the households I visited in Sangrur District – some individuals might be doing ‘outside’ work but, as a source of household income, this is secondary to the selling of buffalo milk. While Gujjars in Chamba ‘look to’ their buffalo and value them, in Punjab they are ‘concentrate on’ their animals and are economically dependent upon them. Though most had been able to purchase land, no Gujjar in the Malerkotla area had turned this to agriculture. A move to Punjab means a move back into ‘pure’ pastoralism.

Figure 3: Dhodi collecting milk from Naudharani Gujjar colony

Out of a herd of 15 buffalo, at any one time five or six adult females might be expected to be producing milk with each giving between two and three litres per day. A family may keep 3 or 4 litres for themselves but the rest can be sold. On my first morning staying at Jan Mohammed’s house at Naudharani I was woken from an uncomfortable night’s sleep by a boy running in to announce the arrival of a dhodi. Dhodis (or sometimes dhojis) are milk buyers and this one’s name was Maulvi Akhtar – a Muslim from Malerkotla city. Abandoning his career with the IPH Department, Maulvi Akhtar had, a decade previously, purchased a motorbike and two 84 litre flagons and made a new life for himself as a buyer and seller of milk. Everyday Maulvi Akhtar drives out at 3am to visit the fifty or so households that he has committed to buy milk from. Normally dhodis will agree to buy milk from a family for ten days after which they deliver payment. Jan Mohammed told us that that the contract can run for longer periods if both sides are happy with the arrangement. The flasks on Maulvi Akhtar’s bike can carry 250 litres at a time (2 x 84 and 2 smaller containers). Maulvi Akhtar said he gives a good price so has a good relationship with the Gujjars. He says these days local farmers are selling less milk and that milk from the Gujjar’s buffalo is ‘more tasty’. Interviewing both sellers and buyers I was given a fairly consistent rate of between 30 and 36rs per kilo of buffalo milk (depending on fat content). A quick calculation suggests that the daily 2 ½ kilos of milk from a typical female buffalo will sell for around 75rs. On a herd of 15 (of which five might be milking) this would suggest a daily income of upwards of 375rs to the buffalo owners. Taking a mark-up of 5 rupee per litre, dhodis sell on the milk they collect to private dairies and to dhabas, hotels, halwais and cheese-makers in Malerkotla city. The remainder goes for a lower price to the Government Dairy (Verka) or one of the big new ‘super-dairys’ where it is pasteurised and packed for sale in one of the big cities of the Punjab. After Maulvi Akhtar had left another (Hindu) dhodi visits the Gujjar colony later in the morning and two more come back in the late afternoon (milking is done twice a day).

Shreya explained to me the importance of milk drinking to Punjabis. In villages people are able to source milk directly from any neighbours and relatives with cows. With urbanisation a new source of demand has arisen which cannot be met by the ‘packet milk’ produced in large dairies. Desi milk, especially buffalo milk, is a premium product and attracts a premium price. But, for the Gujjars who live at Naudharani the sale of milk is only half of the equation that persuaded them to leave their homes in the Saal valley and relocate to Malerkotla. The reason commonly given for leaving Chamba was the cost of fodder. To get a full picture of the economics of the buffalo herding we need to account for the cost of feeding the animals.

An adult buffalo need to eat 10-15 kg of grass and fodder each day. Up in Chamba fodder is gained in a number of ways – Forest Department grazing permits grant to individuals the right to access alpine pastures in the summer months, them, at the end of the monsoon, grass is cut from individually owned reserves (ghasni) and stored for the winter. As we have heard already, many Gujjars in Chamba were finding it increasingly difficult to find fodder in sufficient quantities to feed their buffalo – a legacy of demographic change (with permit pastures and village grazing land split over generations) and tightened restriction on the use of common and forest land. If fodder was in short supply in mountainous Himachal, would herders fare any better in the intensively farmed landscapes of southern Punjab?

Under monsoon fattened clouds I followed Jan Mohammed as he lead his twenty buffalo out in search of grazing. When leaving the colony three or four Gujjar families will move more or less together with their buffalo. When men are not busy elsewhere they will accompany their animals but, otherwise, it is normal for women and children to spend the day walking up to 10 kilometres from Naudharani with a herd. We set off down the road for a few hundred metres and then cut across a patch of scrubby waste land which led to a canal. A wide path took us down the tree lined edge of the canal; the high wall of a dairy lay on our right. After some time we looped back towards the road, crossed it and followed another canal side path at right-angles to the first. Here Jan Mohammed entered into a short conversation with a farmer and then called the herd to descend and eat the remaining green leaves of a field of recently harvested cabbages. The fertilizing power of buffalo dung encourages farmers to entice Gujjars to enter their field after the harvest has been completed. The following day Jan Mohammed did a deal with some farm labourers who were happy for the Gujjar buffalos pick over the leaves of green gourds that had been grown there so long as they helped to collect and stack the wooden poles that they had been grown on. Though each family’s buffalo are kept apart they are close enough together to support one another if there is need. Negotiations over access to farmers’ fields are carried out on the behalf of the all the families moving together and the extra sets of eyes are clearly useful in looking out for one another’s animals and ensuring they don’t stray into neighbouring fields.

Figure 5: With Buffalo in Field near Naudharani

Climbing up from the low-lying fields we found ourselves on a raised railway line. From here a school sports ground was visible with well-dressed young men playing cricket. Next to this was another large patch of lightly grassed waste land to which the buffalo moved after they had finished chewing their way through the cabbage leaves. Jan Mohammed said that the open ground belonged to the owner of school and his buffalo could graze here; as when grazing at the edge of roads, railways and canals the grass found in empty plots of land costs nothing. Though some fields are empty year-round, it is the summer months that grazing is most easily found. However, with herd sizes increasing in the Malerkotla tehsil, it appears that even at this time there is not enough grazing to go around. I visited in early July and found that half of the buffalo in Naudharani had left the colony and been taken on migration to neighbouring Patiala District for two months. There is less grazing to be found in winter. As we watched the buffalos graze, Jan Mohammed went over the different sources of fodder according to the season in which they became available:

Maize and Millet., coarse cereals such as maize (makki) and millet (bajra) play an important role in animal feed supply. Maize is a staple crop in Chamba where it fills multiple needs – eaten on the cob or turned to flour, burned as fuel, sold for cash or, taking and storing the stalks, fed to cattle through the winter months. In Punjab mechanisation and specialisation of agriculture means that only the wrapped cobs of corn are collected leaving the stalks standing. Each August Gujjars are able to cut these stalks and take them back for their buffalo to eat. Sometimes the farmer will ask for money but more often they allow them to take the stalks for free.

Prali (paddy straw). When harvested only the upper part of the paddy is removed and the remainder of the shoot remains in the field. This paddy straw is usually burned by farmers anxious to hasten the planting of the winter wheat crop. Farmers are mostly happy for Gujjars to clear their fields and don’t charge them for it. The only cost is for transportation (usually a bullock cart) and labour (normally the community comes together to collect on a reciprocal basis. During the rice harvesting season (October and November) Gujjars such as Jan Mohammed spent their time ‘picking prali, loading prali and heaping prali’. For the Gujjars’ buffalo prali represents the major source of food over the winter months.

Mustard / rapeseed. This is a rabi crop grown alongside wheat in winter. After pressing has been completed and the oil extracted the leaves are sold to Gujjars at a cheap price (rs5 per kilo) and fed to buffalo.

Berseem. This green leaf vegetable grows so rapidly between November and May that it may be cut 5 or 6 times over these months. In return for help with cutting it the Gujjars are able to claim a share of the cut for their own animals. Jan Mohammed says that in Punjab there is rarely any need to pay for fodder – it’s either free to collect or it can be got by helping to harvest it: ‘those with lots of money opt to pay for it while those that are poor – who only do time-pass – can get it by doing the cutting’

It was mid-afternoon when heavy drops of warm rain began to fall from the sky. In minutes we were soaked. Leaving the buffalo, we walked through flooded rice fields back to the Gujjar colony. The ground there had been transformed into a thick sea of mud and we had to pick our way along a series of strategically placed bricks in order to reach Jan Mohammed’s home.

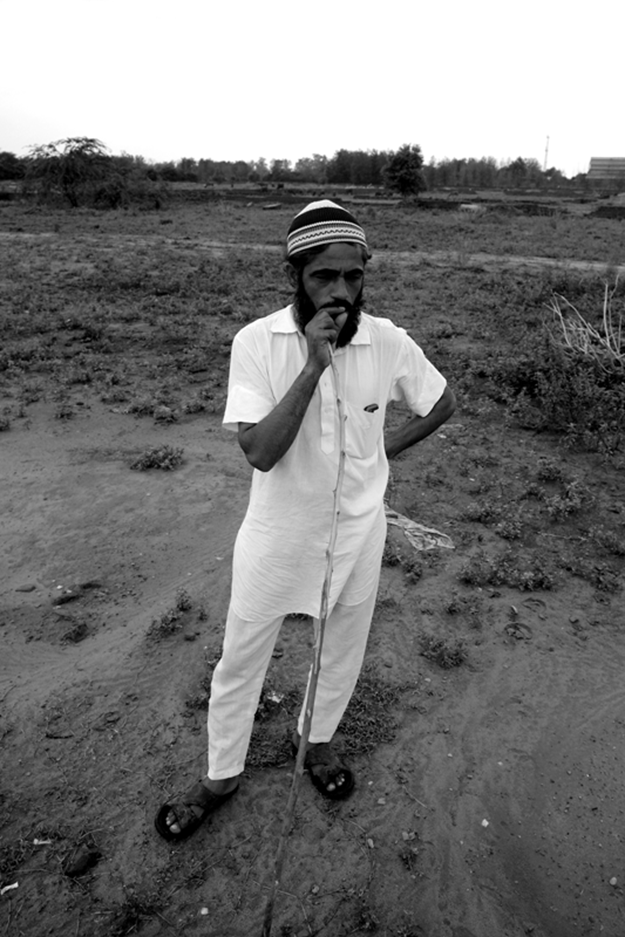

Figure 6: Jan Mohammed Lodhi (with factory in background)

The next morning the buffalo set out on the same route beside the canal but then diverted off in the opposite direction to the one we had taken previously. Here, beside the road, we entered an expanse of waste ground – about 1 km long by 500 metres wide. Here a number of small factory units had been thrown up seemingly at random – one was producing karais; another was preparing to make steel. Compared to other areas in Punjab (including to the north of town) the area to the south of Malerkotla is dotted with empty plots of land such as this and the one seen the previous day next to the school. Given the commercial productivity of agriculture in the area it raises the question of why such valuable land is not being put to use. This move away from agriculture is most obviously apparent on the land bordering the roads that run south from Malerkotla. This side of Malerkotla was, in the early 1980s, declared an industrial zone and provided with upgraded electricity, road and rail connections. From this initial hub, factory development has steadily expanded into the countryside along the Malerkotla-Sanghera and Malerkotla-Sangrur Roads. Conversations with farmers revealed that factory owners were willing to pay 20,000rs per month to rent one bigha of land. With land values constantly rising farmers were choosing to leave fields uncultivated in order to retain the option to rent or sell. Around Naudharani speculation over land started ‘10-15 years back’. So long as plots remained unfarmed and empty these space can be exploited by Gujjars who freely graze their buffalo on them.

When I asked one local landowner what had brought the Gujjars to Malerkotla he replied: ‘because in Kashmir [sic] milk is cheap and prali is expensive but in Punjab milk is expensive and prali is cheap’. Spending these few days with Jan Mohammed and his buffalos it became apparent that he and his fellow Gujjars are applying their profession of buffalo-herding in a very new context. While fodder can be obtained for Chamba’s thick forests, river-side meadows and grassy hills sides, in Punjab animals are fed from crop residues and by-products before being taken to graze on land opened up by urban spread and industrialisation. As agriculture in Punjab has become increasingly commercialised, specialised and mechanised it has created new forms of ‘waste’ – prali, mustard leaves, maize stalks – which are of no value to farmers. At the same time new forms of ‘grazing waste’ have formed out of the speculation over land that has been promoted by industrialisation around the Malerkotla area. The last two decades have seen a rising demand for milk products in Punjab fuelled by a growing urban middle class. These changes – dating back to the late 1970s and escalating through the ‘80s and ‘90s – coincided with the arrival of Gujjars from Chamba who recognised a new niche and set out to exploit it.

Which place is better? Comparing Chamba with Malerkotla

Before I first went to visit Malerkotla my Gujjar friends in Chamba were keen to tell me what would find there. Comparing Punjab with their Chamba home they typically would point to environmental differences: ‘here the air is fresh and the water is cold; in Punjab it is hot, there are lots of mosquitoes’. Hajji Hashim, who has a brother and two sons who have relocated to Malerkotla, complained of his visits there: ‘I didn’t feel comfortable in Punjab – I became ill and had to come back. People from the mountains don’t like heat’. Perhaps significantly it seemed to be the wealthier Gujjars in Chamba who were least persuaded of the virtues of Punjab; Lal Hussain – a policeman – told me that other than selling milk, ‘income sources are zero in Punjab’. In an interview with Alpa and Jens my friend the businessman Kassim Deen reflected that while Gujjars who live in Punjab might be economically better off their economic mobility comes with some social costs attached. In Punjab they have ‘no identity cards, no ST status, their children do not go to school’. Furthermore, they are harassed by the local communities as Muslims and the police as potential terrorists – ‘criminal cases are brought against them, their buffalo are blamed for harming fields and police cases are brought against them’. It was Kassim’s belief that ‘the future is dark’ for those that moved to Punjab.

On arriving in Naudharani I sought out Master Hanif who is the father-in-law of Lal Hussain and paternal uncle to Kassim Deen. 73 year old Master Hanif was the first Gujjar in the Saal valley to matriculate and the first to get a government job. After 30 years working as a school teacher in Chamba District he had retired and come to live in Punjab. Invited into his home we sat on a bed in his reception room as he explained that, in his opinion, the climate of the plains wasn’t so bad as some made out. He pointed to the roof which had been constructed in a system called gadr wallah – two iron girders form the base with wooden plaits laid over them; above the plaits is a thick layer of bricks and above this is a layer of mud: ‘it keeps the house cool’. After some time spent passing on news about ‘home’, I was able to discuss with Master Hanif whether Punjab is the better place for Gujjars to live and if they are happier here. Master Hanif was insistent: ‘the prosperity is here – before it was dal, maize-bread and wheat chapatti now for marriage parties we have tandoori chicken…. 20 years ago people only had bicycles and now they have scooters, coaches and tempos to get around’. Switching to English Mohammed Hanif told us that ‘Punjab has full facilities – marketing, transportation, irrigation and potential of project’. To go to school in Punjab children need a certificate from the HP government which requests the Punjab Education board to accept them as students. Master Hanif, however, was dismissive of government schools in Punjab (‘those in H.P. are better’) and told us that that Gujjar children get a good education in the local Madrassa. But what were they to do with that education? What opportunities are available to young Gujjars growing up in Punjab? While Master Hanif acknowledged that in Himachal the government gives support for ST/SC communities, he was dismissive about the benefits these provided: ‘if you are given these things for free then why work? In Chamba people are mostly vacant. This is the reason they have disputes’. By contrast, in Punjab,

‘there are no government jobs for Gujjars because there are no reservations. But buffalo work is good – you can have 20 or 30 animals against three, four or five in Chamba. And many boys find work as drivers – bus, taxi, tempo – sometimes owning their own vehicle and sometimes driving someone else’s. In Punjab everyone is busy – grazing animals hither and thither, selling milk, and earning money. And because we keep busy there are no disputes and there are no quarrels’.

Clearly when trying to understand the condition of Gujjars’ lives in Punjab it is not sufficient to simply ask those that are best off. In his big house in Umra Tunda I remembered Shaif explaining that inequality was present among Gujjars in Punjab just as it was in Chamba: ‘some live in straw houses and some live in concrete’. For Shaif the purchase of land was the single most important step in establishing yourself in Punjab. To him, ‘land is necessary for success’ because it gives access to government services, secures voting and, importantly, accords a degree of status in the wider society. The Gujjars living in the colony at Naudharani all owned the land on which their houses were built. But dotted around the colony and also in the area to the south – as far as Sangrur – there were others who remained landless. I now offer two case studies of Gujjar families who have been unable to purchase land since leaving Chamba.

Yusuf son of Sher Mohammed: A notable feature of rural Punjab – along with small towns and big fields – are the white-washed neo-classical ranches into which the wealthy Jats have poured the profits of farming. Behind one of these Paladian mansions is the temporary home of 18 year old Yusuf who lives with his father Sher Mohammed, his mother Saira and three sisters aged 9, 3 and 6 months. Yusuf’s house is basic in the extreme – the back and side walls are made of mud but the front is constructed from straw matting; these ‘chan’ houses take their name from their grass roofs. It stands in marked contrast to that of the landlord who lives beside them. Having been invited in we found beneath the thatched roof was a single long room divided into sections for sleeping, cooking and stabling buffalo. On the wall of the house were stylised drawings of flowers and animals and someone had written a poetic couplet – hazaron gham bhi hai ek khushi ke liye; koi apna na hua sari zindagi ke liye. Yusuf is recently married and the decorations were made on the occasion of this wedding.

Figure 7: Yusuf and his sisters

Yusuf told us he had been born in Palyour village but left eight years ago. When they left they had no buffalo. His father’s brothers – Hashim, Bashir and Mohammed Hanif – were all known to me and I had previously conducted a lengthy interview with the family patriarch 95 years old Hajji Alaf Deen. Though by no means wealthy, none of the family in Chamba could be seen as poor – they have large houses close to the road and Hashim and Alaf Deen have both completed the Haaj. That Sher Mohammed had left Chamba without buffalo made me suspect that the cause may have been a family argument over land.

Before coming to Sungrur District there was a period spent living near Amritsar where Yusuf learned to write a little Arabic and Urdu at a Madrassa. Sher Mohammed worked as a labourer and saved up to buy buffalos – the first was given to him as an advance against future work. After three years at Amritsar Sher Mohammed took his family to Pind Baddowal near Jalandhar but they had been forced to leave when their landlord raise the rent demand to 7000rs. They arrived in Sungrur District last year where they pay 5000rs a year to the neighbouring Jat farmer to live on the small patch of land behind his house.

Since leaving Chamba the family have steadily added to their herd and now have ten female buffalo. Yusuf said that some of these animals had been purchased with the help of loans from dhodis – no interest is charged on these loans but sales of resulting milk are guaranteed to the money lender at a sub-market rate. I asked what would happen if they couldn’t make an instalment and Yusuf said would they might be given more time to pay but that ultimately the money lender could come and take the buffalo away. At the moment they are free of debts and, having purchased a motorcycle, Sher Mohammed has started to himself transport to market the milk they produce as well as that of other nearby Gujjar families. Three of their buffalo are young and four are currently pregnant but the remaining females produce between them 9 or 10 litres of milk each day. A quick calculation suggested that the sale of their own buffalos’ milk would generate at least 300rs daily and in addition to this there would be a mark-up of 5rs on the milk purchased from other families and sold in town. Yet Sher Mohammed and his son seemed materially at least to be the poorest Gujjars we met in Punjab. So why are they so poor? They have no land and are dependent on the patronage of local Jats for a place to stay, plus fodder, work and loans. They have no help from government and unlike those living in the Gujjar colony are also cut off from community support networks. Yet I was surprised when I asked Yusuf which place was better and he replied: ‘do you think we could have ten buffalo and a motorbike in Chamba?’ He acknowledged that they didn’t have IRDP status in Punjab and couldn’t buy rice through the PDS system as these rights are tied to the ownership of land. However, Yusuf argued that work is easier to find in Punjab and better remunerated: agricultural labourers are paid almost double what they might get in Chamba; skilled labours can earn 500rs per day (it was pointed out to me that there is little uptake of NREGA due to the ready availability of daily wage work and the fact that the NREGA rate was set at ‘only’ 210rs per day). I asked which place Yusuf thought was best: ‘those who have good employment and income, they are happy in Chamba. But a poor person who has to earn daily wages is better off in Punjab. If it rains in Chamba then that person can’t work and his family are hungry. For poor people it is easier to get work here and better to live here. If you work for 12 hours you can earn 500rs’.

Umar Deen son of Noor Jamal. I first became aware of the migration of Chamba Gujjars to Punjab from my friend Latif who told me that his brother was now living somewhere north of Sangrur town. I was keen to track down this brother so I could compare his life in Punjab with that of Latif who had stayed behind in Chamba. Late one hot April afternoon, as the sun dropped from the sky, Tittu Hussain and I arrived by car outside a large mud-walled chan house beside an open expanse of land on the edge of a large village. Sitting outside the house was a thin man who, the red-dye in his beard apart, bore a close resemblance to Latif. Having confirmed that this was indeed Umar Deen AKA Umro, son of Noor Jamal and brother of Latif Mohammed of Siundi village, we sat on the plastic chairs that had been fetched for us. With the rest of Umro’s family arranged on a nearby charpoi we talked about the process that had brought them here.

Umar Deen told me that he had left Chamba because of ‘lack of grazing land and the expense of buying fodder’. But I knew that there was more to it than that. Umro’s father and mother had divorced leaving Umro and Latif to be raised in their maternal Uncle’s home in Sangera village. Noor Jamal had remarried and his second wife quickly gave birth to two more boys – Yusuf and Dulli (Abdulla) who lived with their father in Siundi village. When Noor Jamal died Latif claimed a share of his father’s land in Siundi but this caused tensions with his half-brothers. Furthermore the inheritance disputed by Latif, Yusuf and Dulli is a right of use only – the fields at Siundi are classified as ‘compensation land’ and remain under the control of the state waqf board. With relatives already established in Punjab, and feeling he had little reason to stay, in 2002 Umar Deen decided to leave Chamba:

‘My uncle lived in Phagwara and through him I was able to get some basic work with Jat families – helping with the harvest plus grazing their buffalo. In return I was given a little cash plus allowed to keep the occasional buffalo calf. We stayed for three years at Phagwara but the land we were living on belonged to the Forest Department and they wanted to build a nursery. So we left that place and after that had one year in Ghelum and Jhikala [near Melarkotla] before coming to this place seven years ago’.

Umar Deen is not the owner of land on which his family live so must pay rent to the landholder. Land, he says, is very expensive – one lakh for one biswa and he could never save the ten or twenty lakh required. Though his eldest son died, three surviving sons still lives with Umar Deen as part of a joint family. The oldest surviving son is 22 years old Rafiq, next is 15 year old Lal Ussain, and then 13 year old Man Ussain. He also has four daughters and cares for the grandchild who is now without a father. When they left Chamba the family had two buffalo and now they have 30. This provides work enough for the family: taking the buffalo to graze every day; in winter cutting berseem, in summer collecting prali in their bullock cart. Rafiq and Lal Ussain each go twice-daily to milk the cattle of neighbouring farmers and for this are paid 4,000rs per month.

Figure 8: Umar Deen and Family

Umar Deen explains that none of his children have attended school because ‘we were moving here and there and never settled for long’. A lack of education in a Gujjar family is not unique to Punjab: back in Himachal Umar Deen’s brother Latif also has seven children of whom only one has seen the inside of a school. The Scheduled Tribe status that Gujjars hold in H.P. does not transfer with them to Punjab. When asked if there would be any advantage in retaining this ST status Umro laughs: ‘if you have no education you don’t get government jobs’. In Punjab as in H.P. iliteracy and poverty stop you from getting government jobs with or without affirmative action.

Given the lack of government support in Punjab I ask about community work – is there any bhaichara here? ‘Nahi – ham akele hai. We have only a link with the [Jat] people living nearby. They may help but it will cost – it’s always on a rent basis’. What asked about tensions with Punjabi people, Umro defended them saying he had always found his Jat neighbours to be ‘helpful and cooperative’. On such a short series of visits it would be impossible for me to get into the fine grain of relations between Gujjar incomers and their Punjabi hosts. What I will say is that in-spite of some pointed questioning none of the Gujjars I interviewed had any complain about police harassment or exploitation by employers while Punjabis said they welcomed the Gujjars as ‘honest and friendly’ neighbours.

Umar Deen was last in Chamba two years ago when he went to see his family. His sons however have never visited Himachal and Umar Deen doubts they would be able to cope with the uphill walks. I ask Umar Deen if he misses anything about Chamba:

‘I have lots of feeling for that place. I miss it but “what to do?” I miss what I did when I was young. In the mountains people live a long life but here in Punjab you don’t live so long. This is because of the scorching heat, the winter cold and the mosquitoes. In Chamba the air is fresh and the water clean’.

Ultimately the difference is a simple one and is down to economic calculus:

‘In Chamba it was not possible to produce six quintals of wheat from the land we had. Here we can go into the fields and pick up the wheat that the farmer has left behind and it comes to more than six quintals. The waste here is greater that the harvest there!’

Himachali Gujjars who don’t own land in Punjab are unable to vote, can’t get a ration card and have difficulty securing electricity or water supplies to their temporary homes. With land prices rising every year it presumably become harder to get hold of land which leaves late-comers condemned to a precarious life of constant uncertainty. However, it may be significant to report that, other than in cases of family breakdown caused by death or divorce, rarely has anyone who left for Punjab come back to live permanently in Chamba. Shaif Mohammed told me that ‘those who work hard will do well here. In Punjab it’s not easy getting started but once you are established the rewards will come to you’. For some it is easier to become established that for others. None-the-less with regard to assets, livelihoods and access to rights it could be argued that the condition of Gujjars are currently no worse – and in some respects considerably better – in Punjab compared to Himachal.

Conclusion: marginality and vulnerability

The Gujjars that left Chamba for Punjab have done so because they identified a new niche into which they could insert their traditional buffalo herding. Buffalo herding in Punjab grew out of the changes unleashed by urbanisation and industrialisation (which creates waste land) and of the development of commercial agriculture (which generates waste produce). Being reliant on waste – whether that means waste land or waste produce – they are marginal to the wider society and economy. It is hard to see these Gujjars, even those who are landless, as being exploited or oppressed because the option of exit – of packing up and moving-on – is always there. Theirs is, if you like, a return to classic nomadism, operating on the margins and exploiting niches that no-one else has claimed and trying to avoid the oppressive relationships they see as coming with settlement.

There is, however, a second issue to address here. What should concern us is the question of just how long this particular niche will remain open. On the whole, the situation of Gujjars in Punjab is better characterised by vulnerability than exploitation. They are vulnerable because the niche they have established themselves is unlikely to be permanent. Falling levels of ground-water could herald a mass move away from the paddy cultivation that gifts prali to the Gujjars; at some point industry will expand into empty plots or farmers might reclaim them for agriculture. In pursuing their ghumantu traditions in Malerkotla might the Chamba Gujjars be heading down a dead-end? Already Gujjars from Malerkotla are starting to travel to Patiala District in the summer to find grazing for their buffalo. Could this be the next stage of the Gujjars migration southward that started from Kashmir more than a century ago?

Epilogue: why did Gujjars stop leaving Chamba after 2005?

After I returned to Chamba from Malerkotla for the second time I continued to find connections between the two places. Punjab and Chamba are not distinct bounded locations; there is a good deal of back and forth between them. Two brothers in Rapari village in the Saal valley have taken wives that were born near Malerkotla; Yusuf the young man who married the week before I met him in Sungrur District said his new wife was from near Palyor. There is now a mini-bus service that runs directly between Naudharani and Saho at the head of the Saal valley. Fateh Mohammed – the first Gujjar to leave Chamba for Malerkotla – became wealthy and returned to provide the finance for the new Madrassa at Saho. But it was this interview that got me thinking about why Gujjars stopped leaving Chamba after 2005.

Fieldnotes from the afternoon of 27th July. “Khan wanted to visit Gulam Rasul Lodhi and as we were in the area and I also wanted to talk to him I went along with. Anyway with a lot of effort on my part, I was able to determine the economics of GRL’s prali importing business. GR Lodhi has two trucks one of which can carry 10-12 quintals of prali and the other 20 quintals. For the months of September and October GRL makes multiple trips down to Gurdaspur and Dingwara where high quality Prali is available cheaply (he said the quality in Melarkhotla and Pagwara isn’t so good and it’s much further away though he’ll go there if he can’t find prali elsewhere). There is now a law against the burning of prali as it is polluting so farmers are keen to sell. Rice straw from 1 qila of land will fill the small tuck (12 quintals) while the big truck can carry prali from a field of 1 ½ to 1 ¾ qilas in size (20 quintals). During the two month rice harvest season he will travel with these two trucks forty or fifty times down to Punjab – leaving Chamba in the morning and loading in the evening, then sleeping and returning to Chamba the next day). It costs 2-3000rs to buy the prali from 1 qila of land (so the cost of the rice from 2 ½ qilas that fills the two trucks would be about 7000rs). Cost of loading plus fuel and road taxes adds up to 10,000 per truck, per trip. But a truck load of prali will sell for 18,000 in around Chamba, Tissa, Rakh, Saho, Palyor and also Kangra. So the per truck profit will be about 5000rs for a two day trip. He said he has no problems with the police in Punjab: ‘there is no tension – in season hundreds of trucks are passing through Punjab so why should they bother me?’ GRL is not alone in importing prali to Chamba. He estimates there are 20 other Gujjars and 10-15 Mahajans also – maybe a total of 2000 truckloads. Half of these Gujjars own their own vehicle and the others drive for someone else. ‘It is because of us bringing prali to Chamba that the migration of Gujjars from here to Punjab has halted. The high water mark of migration to Punjab was 1995-2005. Lodhi has been importing prali for 10 years – he started around about the same time that Gujjars stopped migrating out of Chamba. The other major change that happened around this time was the building of the power house’

Through the construction of the power house at Palyor some Gujjars (the better educated and wealthy) established themselves as contractors while others (the poorer ones that hadn’t been to school) started to find work as labourers on hydro-projects in Chamba and elsewhere. But that’s a story for another time.